Former Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who governed the South Asian country for two terms and liberalised its economy in an earlier stint as finance minister, has died. He was 92.

Singh, an economist-turned-politician who also served as the governor of the Central Bank of India, was ailing and admitted to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi late on Thursday.

His health deteriorated due to “sudden loss of consciousness at home”, the hospital said in a statement. He was “being treated for age-related medical conditions”, the statement added.

A mild-mannered technocrat, Singh became one of India’s longest serving prime ministers, holding the office from 2004 to 2014 and earning a reputation as a man of great personal integrity.

Singh adopted a low profile after relinquishing the post of prime minister. He is survived by his wife and three daughters.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who succeeded Singh in 2014, called him one of India’s “most distinguished leaders” who rose from humble origins and left “a strong imprint on our economic policy over the years”.

Advertisement

“As our Prime Minister, he made extensive efforts to improve people’s lives,” Modi said in a post on X. He called Singh’s interventions in parliament as a lawmaker “insightful” and said “his wisdom and humility were always visible”.

Born in 1932 into a poor family in a part of British-ruled India now in Pakistan, Singh studied by candlelight to win a place at Cambridge University before heading to Oxford, earning a doctorate with a thesis on the role of exports and free trade in India’s economy.

He became a respected economist, then India’s Central Bank governor and a government adviser but had no apparent plans for a political career when he was suddenly tapped to become finance minister in 1991.

During that tenure to 1996, Singh was the architect of reforms that saved India’s economy from a severe balance of payments crisis and promoted deregulation and other measures that opened an insular country to the world.

Advertisement

Singh’s ascension to prime minister in 2004 was even more unexpected.

He was asked to take on the job by Sonia Gandhi after she led the centre-left Indian National Congress party to a surprise victory. Italian by birth, she feared her ancestry would be used by Hindu-nationalist opponents to attack the government if she were to lead the country.

Riding an unprecedented period of economic growth, Singh’s government shared the spoils of the country’s new-found wealth, introducing welfare schemes such as a jobs programme for the rural poor.

In 2008, his government also clinched a landmark deal that permitted peaceful trade in nuclear energy with the United States for the first time in three decades, paving the way for strong relations between New Delhi and Washington.

However, his efforts to further open up the Indian economy were frequently frustrated by political wrangling within his own party and demands made by coalition partners.

In 2012, his government was tipped into a minority after the Congress party’s biggest ally quit their coalition in protest at the entry of foreign supermarkets. Two years later, Congress was decisively swept aside by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party.

At a news conference months before he left office, Singh insisted he had done the best he could for the country.

“I honestly believe that history will be kinder to me than the contemporary media or, for that matter, the opposition parties in parliament,” he said.

Related News

How India’s Gukesh Dommaraju became chess king in a cricket crazy country

Erdogan urges end of foreign support for Kurdish fighters in Syria

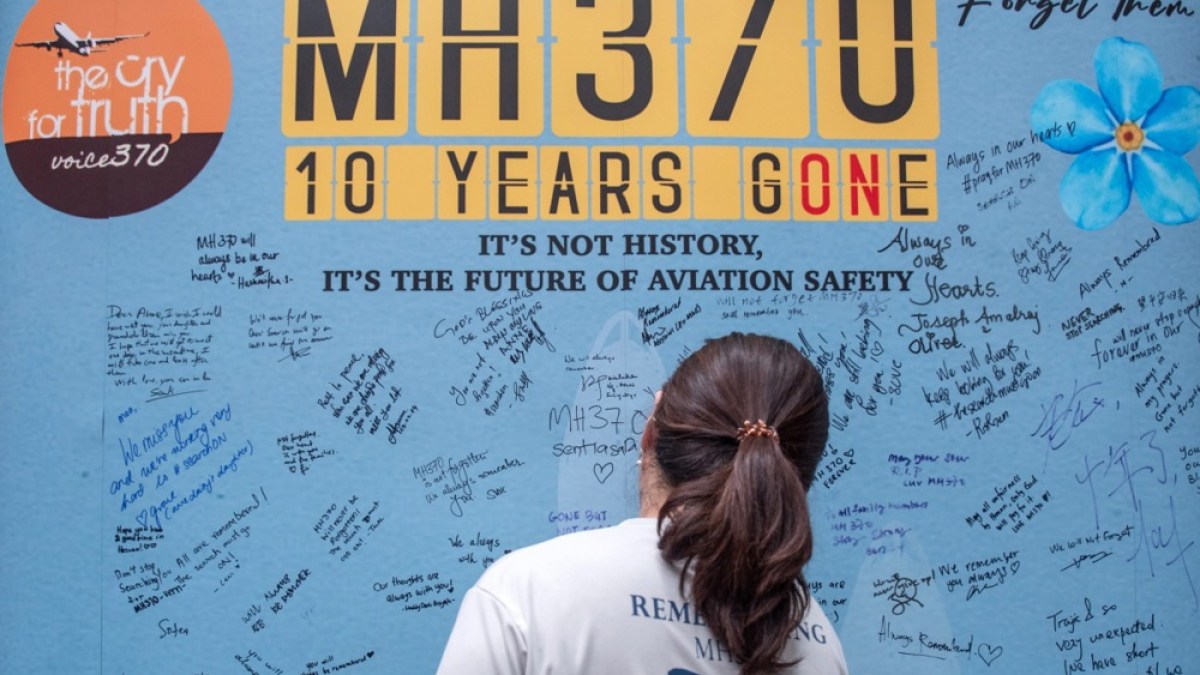

Malaysia to resume search for missing MH370